The Business of Making Dance

INterview with Brendan Duggan

I have to confess,” I told Brendan after we hugged hello, “I didn’t do a site visit this early in the morning. The lighting isn’t as good as it will be — would you mind doing the interview first?”

“No problem”, he answered as we sat down on the steps of Rhino’s pedestrian crosswalk. I propped up my phone as close to Brendan as I could, hoping the sound of passing trains didn’t drown out his voice.

“Let me run these questions by you?” My voice tilts up unnecessarily, betraying my slight nervousness. This was my first interview. I’d choose Brendan deliberately because of his encouraging and gentle demeanor.

And because — of all my interviewees — I knew him best.

I met Brendan last spring after auditioning and being cast in his latest Immersive theater production “From On High”. We talked about many things during the interview including the genesis of Oddknock — the production company he created alongside Parker Murphey and Zack Martens — why they decided to move to Denver (from NYC) to start Oddknock, and what they’d learned from the successes and failures of their first major production. But the moment that stuck with me as I walked away from our interview was when we’d stumbled onto the topic of creating dance using a nonprofit vs for-profit model.

Natalia, “So then — I just didn't even realize — are most of the big, big, big shows that I think of (that aren’t concert dance) for-profit shows?”

Brendan, “Most of the traditional Broadway shows you think about are all for profit shows. They have arrangements with the different Theater spaces in New York to inhabit their space. They have a budget [of] $4 million or so to make the show.

As you've seen most Broadway shows don't stay open for longer than a few months, but their profit model is built in a way that they can still break even off of that short amount of time. Or they don’t, and they close."

Natalia, “So then… I wonder if you can talk about what it was like to be a nonprofit company with Loud hound [dance] versus a for-profit arts company.”

Brendan, “Being a part of the not-for-profit world and being a part of the arts worlds… the blueprint of how you make art is that you apply for grants, you apply for residencies, you just try and write and write and write applications to get your stuff seen and supported.

“And… What I was finding was that the type of work that I wanted to make (and frankly the type of identity that I have as a white, straight male) was not finding any traction in a lot of these grants proposals. That's totally fine, that's the way those things work. But I was seeing this cap to what I wanted to do and the scale at which I wanted to do it."

“I felt that I really needed to reconsider how my work was funded and how it was perceived so that I didn’t feel like I was too wrapped up in value structures that I was trying to force. I'm not making a show about climate justice because I'm not passionate about that topic in my personal life… and I don't want to force myself to fit into that category if I don't really, truly, believe that deep down in my bones. Maybe parts of what I do touches on my perspective on climate, but not in a way that's like: this is about The Drought. I felt a lot of resistance from the nonprofit structure. So I wanted to take some space and think about my work more holistically.”

At this moment in the conversation, I had to take a beat. I was shocked. Not that Brendan was a straight, white male — as unusual as that is in the dance world — but because the work that he and Oddknock are creating is completely unsupported by the nonprofit world.

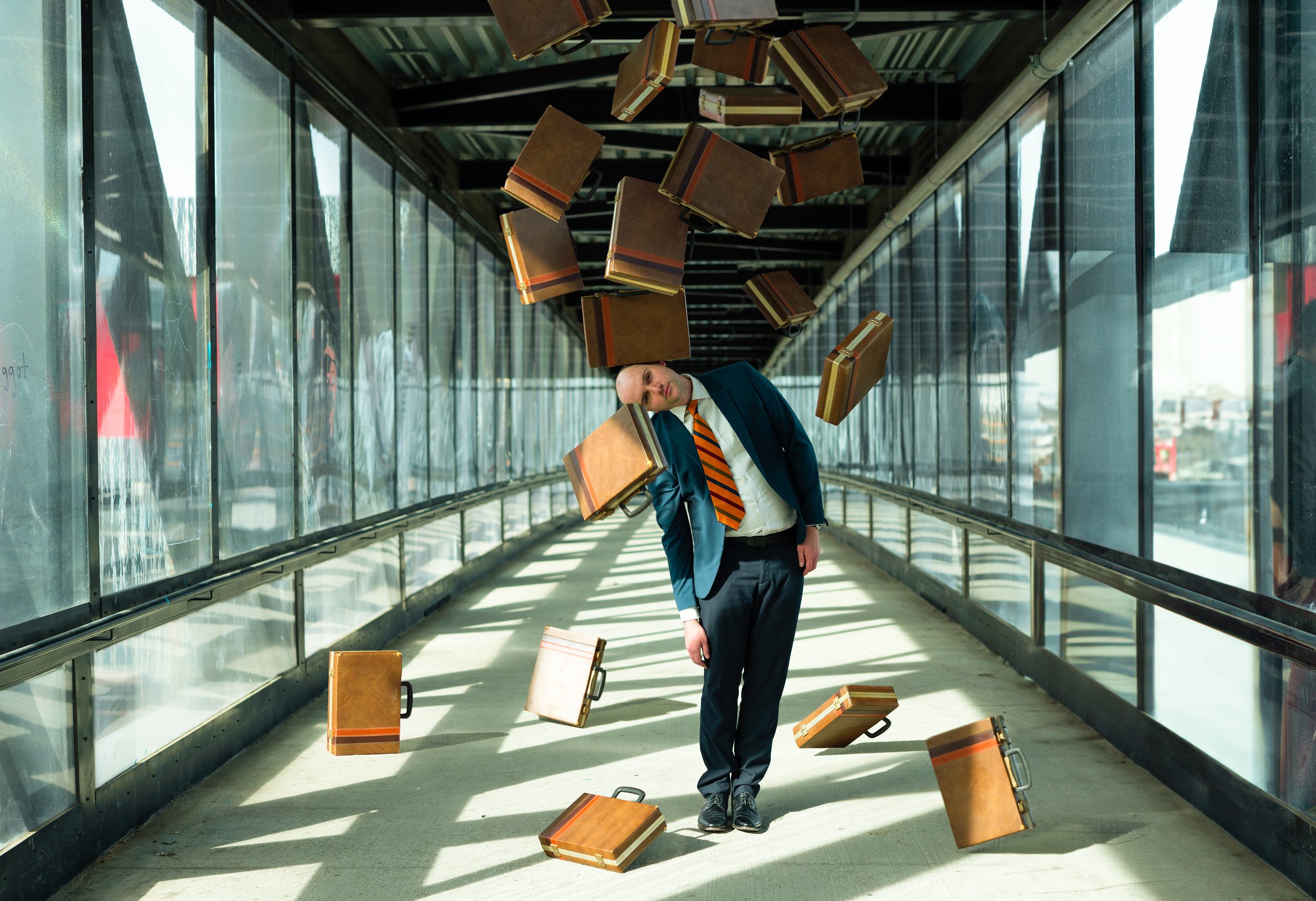

From On High was the most amazing experience I have ever had as a performer. For the first time I was provided with a living wage. I was able to solely perform without having to supplement my income with teaching, filmmaking, or a thousand other small jobs. This was ongoing work — not just for a weekend, a week or a month. And it wasn’t ballet or broadway— it was using contemporary dance in a new genre of theater outside of NYC. I was trusted and allowed to constantly develop and enrich my character, my script and my dance within the work. I was in an environment, and amongst a cast, that inspired me to do so. The work was funny and absurd but also touched on deep societal issues such as capitalism, the kind of blind faith that leads to zealots, and the many-faceted ways we sacrifice our personal humanity to become a part of inhumane structures. In a cast of 6 people, 3 were BIPOC and 2 were trans — yet that fact was never emphasized, used or… the goal of the work. It simply was. The goal was to create great art.

When I asked Brendan why he, Parker and Zach started Oddknock he answered, “to be frank, our initial motivation for starting this company was that we had had such terrible experiences at Sleep No More… we felt invisible in that space, despite the ambitious creative projects that we were undertaking. We really wanted to see if there was a different way to make immersive theater at a large scale and still treat everyone the way they should be treated (…) and still make money on top of all of that.”

When I asked him what motivated him to make art he answered, “One of the reasons I make Performances that interact with other people and engage with other people is that… I really feel like there's a value in connecting everyone to performance: to dance, to theater, to art. And I feel like a lot of times — especially with dance — there’s such a translation miscommunication. A lot of people don't know how to engage with it or talk about it without saying, “the dancers are really pretty” or “Oh, that was so cool when she did that thing” or “Oh, I thought it was about this”— which is the most adventurous you’ll get.

“I really wanted to find ways to get dance — really high level dance — in the right environment so that it's received well and people feel like they can talk about it. And talk about the story they saw, and the context, and how it made them feel… and not feel like they're outsiders.

“That is [the] number one [reason]. Number two kind of builds on that — I feel like there's a lot of healing power with the kind of interactive performances where people get a chance to really communicate with an art form and have it communicate back to them. Who they might be or what they might be capable of.

“Great examples are live action, role play things where people lose themselves in some fantasy character and just get to be a hero for a day. I love that! It brings this pure childlike joy to somebody to feel like, “I'm playing the game and I'm crushing it right now and everyone knows it. In my normal life, I don't really feel seen or understood the way I feel seen and understand here.”

Making art accessible. Combating social isolation. Creating a living wage for artists outside of NYC or LA. Personally, I think these are huge issues that need to be tackled alongside issues of climate change and gender binaries. It’s not a ‘one or the other’ issue because creating art that connects us and reminds us of our humanity is essential work. Creating conditions for artists to be able to do this is essential work. And the fact that this kind of work is more supported by the for-profit than the non-profit sectors is, I think, a massive issue we have to look at.